Fight and unite: Leveraging Conflict for Better Decisions

I’ve led and been on a lot of teams. I have worked on healthy teams and dysfunctional teams. One of the things that differentiates the two is how they do conflict.

This week I enjoyed learning about doing conflict as a team from consultants from The Table Group. The founder of The Table Group, Patrick Lencioni, has written many books on organizational health. His book The Five Dysfunctions of a Team describes five behaviors of a dysfunctional team. Healthy teams address these dysfunctions and practice healthy behaviors.

One of these behaviors is mining for conflict, or actively seeking out opposing ideas and disagreement. This enables the decision maker(s) to understand all the variables and make the best decision possible.

The discussions with our facilitators led to my reflecting on the different teams of which I have been a part. Below is a mash-up of what our facilitators taught, my reflections and learnings from other experiences, and, of course, fun doodles! Some were healthy; some were not. All of them were great grounds for learning.

Contrasting Conflict Styles

On healthy teams, conflict is open. People sit around the table and disagree with each other. The conflict is not personal but focused on the issue. There are debates and disagreements and discussions of perspectives.

In dysfunctional teams, the conflict goes underground or sideways. During the meeting, people look like they get along or are fine with things. But there are offline conversations, people who secretly disagree with others on the team, and a lack of openly discussing the disagreements. Trust breaks down.

How Conflicts Relate to Decision-making

Why is it important for teams to have conflict? Conflicts enable us to make faster, better decisions. Conflict helps bring information to light so that the decision can be made faster. It is a better-informed decision because of the input of others.

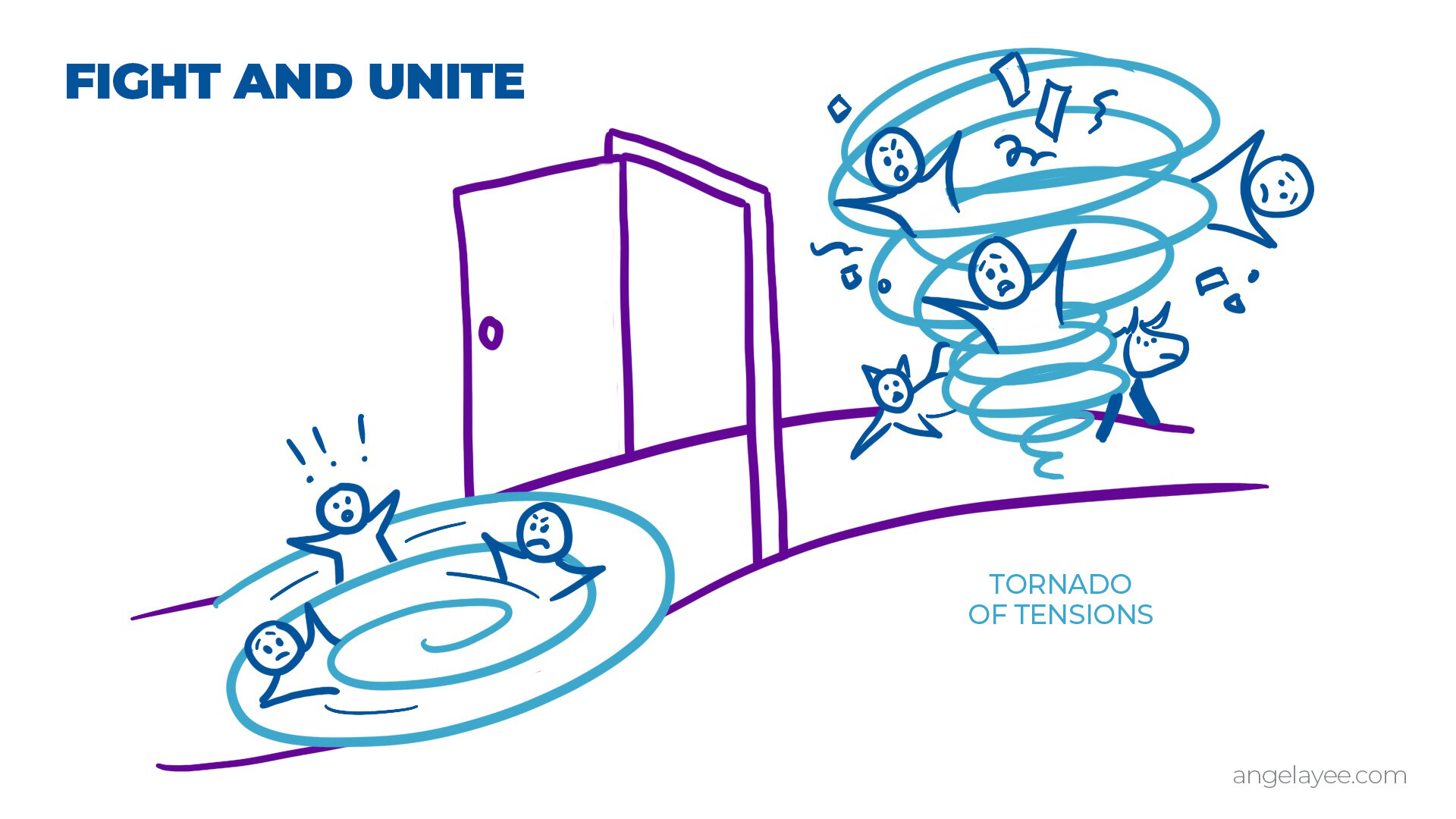

On teams, either the decision is made by the leader (in which case the team gives input), or the team as a whole makes a decision. Eventually, the decision-maker(s) walk through the Door of Decision (hopefully!). The decision is made, and it is now time to start implementing.

However, for dysfunctional teams, getting through that door is not so easy.

On dysfunctional teams, the debate becomes unproductive and gets stuck, so there is no resolution or outcome. The team talks and disagrees behind the scenes or openly, but they cannot resolve the issue.

The Table Group facilitators call it “the swirl.” My team leader calls it the “doom loop.” I think of it as a whirlpool. The energy gets sucked down the vortex, and the joy and enthusiasm become depleted.

The reasons are myriad why the team is trapped in a whirlpool: a lack of trust, lack of alignment on direction, silence leading to conflict going underground, strained relationships, strong egos, lack of information, inability to make decisions — the list goes on! It’s not a fun place to be and is utterly exhausting. The team experiences constant conflict with little progress.

A team that doesn’t learn how to leverage conflict and put boundaries around it can also find that the conflict expands. Not only is there conflict before the decision, but there is also conflict after walking through the Door of Decision.

Those who were not keen on the decision keep wanting to debate it. The whirlpool is repeatedly brought in other meetings. There are more offline conversations about why that decision should not have been made, or things should have been done differently. Some team members go around telling people outside of the team why they disagreed with the decision.

After walking through the Door of Decision, any subsequent conflict turns into a tornado. Like a real-life massive whirlwind, the tensions cause carnage. People feel hurt, relationships are broken, and the decision that was made faces problems getting implemented. A path of wreckage and casualties is strewn behind the tornado.

In a sense, the tension is understandable. After all, no one agrees 100% all the time with the leader, and someone is bound to disagree, especially if the leader makes a call that you don’t like. But there is a principle that is key for teams to function healthily even if some disagree:

Fight BEFORE the decision.

Unite AFTER the decision.

I didn’t make up the phrase “fight and unite” — I’m not sure who made it up. But it’s a great phrase to remember how to act as a healthy team.

The key to having the best decision made in the time that it needs to be made is for the team to engage in conflict before the decision is made. The team must engage in a “lightning storm” conflict — sparks may fly, but the light of ideas clashing with ideas brings insights on the decision to be made.

As a team leader or member, you must not see the “fight” as a challenge to your authority to your ego, but as an exercise to burn away the flawed ideas and hone the decision-making into the best outcome that can be discerned with the team’s input. It is a way for the team to pull together and say, “We’re working as a team to have each other’s backs to protect each other from making dumb decisions.”

Fight, then walk through the Door of Decision, and close it.

Once the decision is made, it is time to unite. If you don’t like the decision, you must “disagree and commit” (another phrase I didn’t make up but that is a general management principle). To disagree and commit means that you have been open, honest, and compelling in the debate before the decision is made. You brought up all the reasons and perspectives for alternative decisions.

But once the decision is made, even though you may not entirely agree with it, you take one for the team. You place the good of the team before yourself, and you commit to that decision. You act on it as if you fully own it.

Is this hard? Yes! But a team that keeps trying to open up that door and revisit the past ends up back again in the whirlpool. The decision door stays closed, and the team moves forward.

The Caveats

What I described above is the ideal situation. Debate before the decision, and once the decision is made, get on board and move forward. However, there are a few exceptions.

Sometimes a decision is made, and new information comes up that changes the picture. In that case, the decision can be rethought and considered. Or, after beginning implementation, new learnings arise that require the decision to be adjusted. The decision-maker(s) would have the freedom to tweak the decision (after mining for conflict if the change is significant). Once that new decision is made, the rest of the team once again commits to the new direction.

There’s another caveat — sometimes there are leaders and teams who just make bad decisions. That’s a tough place to be. If you find that over time you feel you cannot disagree and commit, it is time to start considering whether you should seek another opportunity. If your conscience or values continue to be violated, staying in such a place is not healthy for you or for the team and organization. (See The Conviction Core for a tool to help you think through if you should stay or leave.)

But when you’re aligned with the rest of the team — wow! The team’s effectiveness and health skyrocket to heights you may never imagined.

——————-

Find this helpful? Subscribe for more articles!